Early Diagnosis

Children with Autism can be diagnosed from the age of 2 or sometimes younger.

The Earlier the Diagnosis the better the prognosis early diagnosis means that parents can make sense of any difficulties their child has experienced in their development and can seek the correct help and intervention to improve outcomes for their child, and for them and a family.

Not every autistic person is diagnosed early however, diagnosis even in adulthood can help to gain access to support and services as well as providing explanation to

situations and characteristics which can be difficult to understand.

Research over time has been an improved understanding of Autism, however there are

still many questions which remain unanswered. Research is the essential key to improving knowledge and understanding, from which professionals can ensure that new and breaking information can be used to best advantage in supporting children and adults with Autism, and their families.

The sharing of scientific research worldwide provides opportunities for exchange of

reliable information and positive intervention and outcomes.

Autism is a lifelong disability that affects how a person makes sense of the world,

processes information and relates to other people.

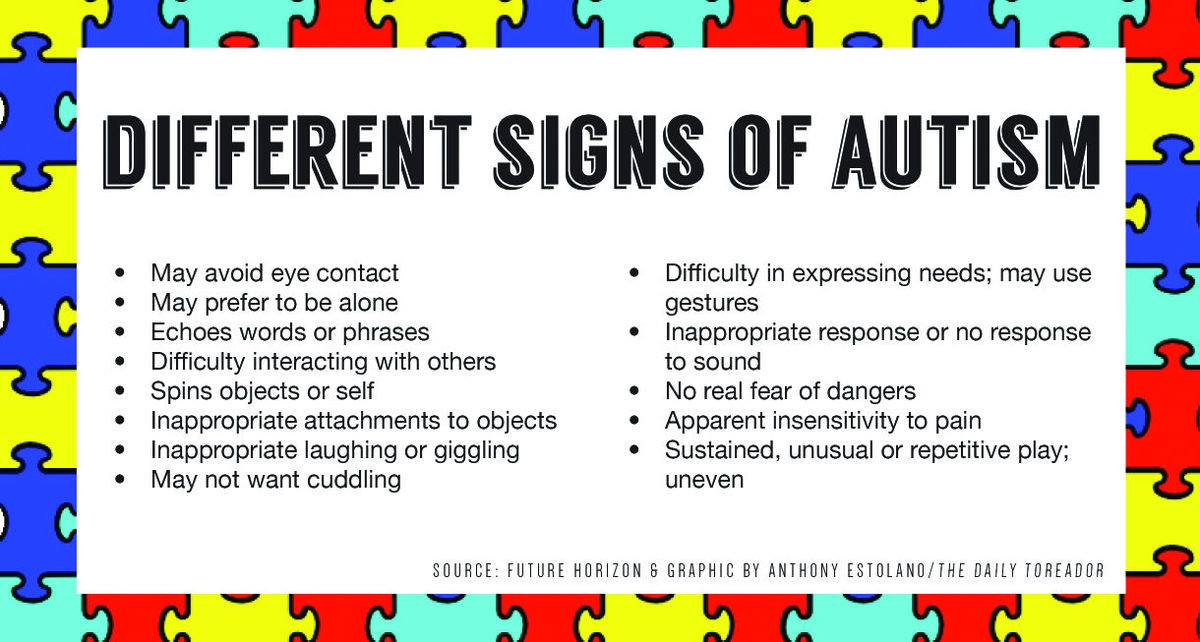

The three main areas of difficulty which all people with autism share are sometimes known as the triad of impairments, which are:

1) Difficulty with social communication

2) Difficulty with social interaction

3) Difficulty with social imagination.

Accompanied by obsessions, ritualistic behavior and difficulties with change, and various sensory sensitivities.

These characteristics vary in presentation from person to person, although they

will be clearly identifiable.

“I have twin boys both non verbal . Double the challenges but both with different problems. We are very worried about the future.”

Behaviour

Autistic people may appear to behave unusually. There will generally be a reason for this: it can be an attempt to communicate, or a way of coping with a particular situation.

Knowing what causes challenging behaviour can help you to develop ways of dealing with it. You’ll find practical information and tips in this section.

Sensory differences

Many people on the autism spectrum have difficulty processing everyday sensory information. Any of the senses may be over- or under-sensitive, or both, at different times. These sensory differences can affect behaviour, and can have a profound effect on a person’s life. Here we help you to understand , the person and how to help. You can also find out about therapies and equipment.

Too much information

Sometimes an autistic person may behave in a way that you wouldn't immediately link to sensory sensitivities. A person who struggles to deal with everyday sensory information can experience sensory overload, or information overload. Too much information can cause stress, anxiety, and possibly physical pain. This can result in withdrawal, challenging behaviour or meltdown.

If I get sensory overload then I just shut down; you get what's known as fragmentation...it's weird, like being tuned into 40 TV channels.

If someone is having a meltdown, or not responding, don’t judge them. There are things can happen. This can make a world of difference to someone with autism and their carers.

Often, small changes to the environment can make a difference. Creating a sensory profile may help you to work out what changes are needed. Three points to remember are:

be aware. Look at the environment to see if it is creating difficulties. Can you change anything?

be creative. Think of some positive sensory experiences.

be prepared. Tell the person about possible sensory stimuli they may experience in different environments.

Sensory sensitivities

UNDER-SENSITIVE

Objects appear quite dark, or lose some of their features.

Central vision is blurred but peripheral vision quite sharp.

A central object is magnified but things on the periphery are blurred.

Poor depth perception, problems with throwing and catching, clumsiness.

Ways you might help include the use of visual supports or coloured lenses , although there is only very limited research evidence for such lenses.

OVER-SENSITIVE

Distorted vision - objects and bright lights can appear to jump around.

Images may fragment.

Easier and more pleasurable to focus on a detail rather than the whole object.

Has difficulty getting to sleep as sensitive to the light.

She was Mrs Marek, a face upon which light danced maniacally, turning her into more of a cartoon than a human being. Welcome to Toon town…I'd like you to enter this torture chamber I call my kitchen and meet my wife who is a 3D cartoon.

You could make changes to the environment such reducing fluorescent lighting, providing sunglasses, using blackout curtains, creating a workstation in the classroom - a space or desk with high walls or divides on both sides to block out visual distractions, using blackout curtains.

- Sound

UNDER-SENSITIVE

May only hear sounds in one ear, the other ear having only partial hearing or none at all.

May not acknowledge particular sounds.

Might enjoy crowded, noisy places or bang doors and objects.

You could help by using visual supports to back up verbal information, and ensuring that other people are aware of the under-sensitivity so that they can communicate effectively. You could ensure that the experiences they enjoy are included in their daily timetable, to ensure this sensory need is met.

OVER-SENSITIVE

Noise can be magnified and sounds become distorted and muddled.

May be able to hear conversations in the distance.

Inability to cut out sounds – notably background noise, leading to difficulties concentrating.

Do you hear noise in your head? It pounds and screeches. Like a train rumbling through your ears.

You could help by:

shutting doors and windows to reduce external sounds

preparing the person before going to noisy or crowded places

providing ear plugs and music to listen to

creating a screened workstation in the classroom or office, positioning the person away from doors and windows.

- Smell

UNDER-SENSITIVE

Some people have no sense of smell and fail to notice extreme odours (this can include their own body odour).

Some people may lick things to get a better sense of what they are.

You could help by creating a routine around regular washing and using strong-smelling products to distract people from inappropriate strong-smelling stimuli (like faeces).

OVER-SENSITIVE

Smells can be intense and overpowering. This can cause toileting probelms

Dislikes people with distinctive perfumes, shampoos, etc.

Smells like dogs, cats, deodorant and aftershave lotion are so strong to me I can't stand it, and perfume drives me nuts.

You could help by using unscented detergents or shampoos, avoiding wearing perfume, and making the environment as fragrance-free as possible.

- Taste

UNDER-SENSITIVE

Likes very spicy foods.

Eats or mouths non-edible items such as stones, dirt, soil, grass, metal, faeces. This is known as pica

OVER-SENSITIVE

Finds some flavours and foods too strong and overpowering because of very sensitive taste buds. Has a restricted diet

Certain textures cause discomfort - may only eat smooth foods like mashed potatoes or ice-cream.

Some autistic people may limit themselves to bland foods or crave very strong-tasting food. As long as someone has some dietary variety, this isn't necessarily a problem. Find out more about over eating and restricted diets.

- Touch

UNDER-SENSITIVE

Holds others tightly - needs to do so before there is a sensation of having applied any pressure.

Has a high pain threshold.

May be unable to feel food in the mouth.

May self harm.

Enjoys heavy objects (eg weighted blankets) on top of them.

Smears faeces as enjoys the texture.

Chews on everything, including clothing and inedible objects.

You could help by:

for smearing, offering alternatives to handle with similar textures, such as jelly, or cornflour and water

for chewing, offering latex-free tubes, straws or hard sweets (chill in the fridge).

OVER-SENSITIVE

Touch can be painful and uncomfortable - people may not like to be touched and this can affect their relationships with others.

Dislikes having anything on hands or feet.

Difficulties brushing and washing hair because head is sensitive.

May find many food textures uncomfortable.

Only tolerates certain types of clothing or textures.

Every time I am touched it hurts; it feels like fire running through my body.

You could help by:

warning the person if you are about to touch them - always approach them from the front

remembering that a hug may be painful rather than comforting

changing the texture of food (eg purée it)

slowly introducing different textures around the person's mouth, such as a flannel, a toothbrush and some different foods

gradually introducing different textures to touch, eg have a box of materials available

allowing a person to complete activities themselves (eg hair brushing and washing) so that they can do what is comfortable for them

turning clothes inside out so there is no seam, removing any tags or labels

allowing the person to wear clothes they're comfortable in.

- Balance (vestibular)

UNDER-SENSITIVE

A need to rock, swing or spin to get some sensory input.

You could encourage activities that help to develop the vestibular system. This could include using rocking horses, swings, roundabouts, seesaws, catching a ball or practising walking smoothly up steps or curbs.

OVER-SENSITIVE

Difficulties with activities like sport, where we need to control our movements.

Difficulties stopping quickly or during an activity.

Car sickness.

Difficulties with activities where the head is not upright or feet are off the ground.

You could help by breaking down activities into small, more easily manageable steps and using visual cues such as a finish line.

- Body awareness (proprioception)

Our body awareness system tells us where our bodies are in space, and how different body parts are moving.

UNDER-SENSITIVE

Stands too close to others, because they cannot measure their proximity to other people and judge personal space.

Finds it hard to navigate rooms and avoid obstructions.

May bump into people.

You could help by:

positioning furniture around the edge of a room to make navigation easier

using weighted blankets to provide deep pressure

putting coloured tape on the floor to indicate boundaries

using the 'arm's-length rule' to judge personal space - this means standing an arm's length away from other people.

OVER-SENSITIVE

Difficulties with fine motor skills, eg manipulating small objects like buttons or shoe laces.

Moves whole body to look at something.

You could help by offering 'fine motor' activities like lacing boards

Synaesthesia

Synaesthesia is a rare condition experienced by some people on the autism spectrum. An experience goes in through one sensory system and out through another. So a person might hear a sound but experience it as a colour. In other words, they will 'hear' the colour blue. Find out more about Synaesthesia.

Therapies and equipment

We can’t make recommendations as to the effectiveness of individual therapies and inteventations or equipment. Research Autism provides free information about autism therapies and interventions.

Music Therapists use instruments and sounds to develop people's sensory systems, usually their auditory (hearing) systems.

Occupational design programmes and often make changes to the environment so that people with sensory difficulties can live as independently as possible.

Speech and vocal therapists often use sensory stimuli to encourage and support the development of language and interaction.

Some people say they find coloured filters helpful, although there is only very limited research evidence.

Behaviour-top tips

Here, we offer some top tips to minimise difficult behaviour and to identify the behaviour's purpose or function , and tell you how you can get support , further information and resources.

Each person and situation is unique. Not all information here will be relevant to everyone on the autism spectrum. It may seem as though the difficult behaviour is only ever directed at you - especially if it tends to happen at home, not at school. You are not the only one in this situation, although we know it can sometimes feel that way.

Identify the behaviour's purpose

Behaviour has a purpose.

It can be a way of communicating needs and feelings. It is important to rule out any medical or dental issues first, particularly if behaviour has started suddenly and become more intense. The person may feel unwell, tired, hungry, thirsty or uncomfortable. Biting may be due to pain in the mouth, teeth or jaw. Spitting may be related to a difficulty with swallowing or to producing too much saliva. Ear slapping or head banging may be a way of coping with pain or communicating discomfort. Aggression may be due to adolescent hormonal changes.

Visit the doctor or dentist and seek a referral to a specialist with experience of autism if needed. Bring along any notes about when the behaviour happens (ie what time of day and in which situations), how often it happens, when it first started, and how long it lasts.

If medical issues have been ruled out, then everyone involved in the person's care can work on completing a behaviour trial . This should include date, time, place, what occurred before, during and after the behaviour, how the person was feeling and how people responded to the behaviour. A diary may be completed over a couple of weeks or longer if needed. Alternatively, completing a functional analyis questionaire could help you to understand the behaviour's purpose and understand triggers. Consider whether any changes, however small, have occurred in the person's routine or timetable which could affect their behaviour.

Top tips

Be patient and realistic

The behaviour generally won't change overnight. Tracking the behaviour in a diary may make it easier to notice small, positive change. Be realistic and set achievable goals.

Choose two behaviours to focus on at a time. Using too many new strategies at once may result in none of them working. Don't worry if things seem to get worse before they get better. It's important to continue with the strategies you are using.

Be consistent

If patterns of behaviour have emerged from the diary, a behaviour plan can be put in place. It's important that everyone involved has a consistent approach to the behaviour and regularly discusses how strategies are progressing.

Consider the sensory environment

Many people on the autism spectrum have difficulty processing everyday sensory information . Some may find it difficult to block out background noise and what they experience as excessive visual information. Some might not be able to manage some tastes or food textures, or find that someone touching them - even lightly - is painful. Others may be drawn to sensory stimuli that they find particularly pleasing.

Autistic people can be very sensitive to subtle changes in their environment . If there's a sudden change in behaviour, think about whether there has been a recent change in the environment.

Support effective communication

Some autistic people can have difficulty making themselves understood, understanding what's being said to them and asked of them, and understanding facial expressions and body language. Even those who speak quite fluently may struggle to tell you something when they are anxious or upset. This can cause considerable frustration and anxiety which may result in difficult, sometimes challenging behaviour .

Speak clearly and precisely using short sentences. By limiting your communication , the person is less likely to feel overloaded by information and more likely to be able to process what you say. Autistic people often find it easier to process visual information. Support the person to communicate their wants, needs and physical pain or discomfort, eg by using visual stress scales , PECS , pictures of body parts, symbols for symptons, or pain scales, pain charts or apps.

Help to identify emotions

Many autistic people have difficulty with abstract concepts such as emotions, but there are ways to turn emotions into more 'concrete' concepts, eg by using stress scales. You can use a traffic light system, visual thermometer, or a scale of 1-5 to present emotions as colours or numbers. For example, a green traffic light or a number 1 can mean 'I am calm'; a red traffic light or number 5, 'I am angry'. You could help the person to understand what 'angry' means. One way to do this is to refer to physical changes in the body. For example, 'When I'm angry, my tummy hurts/my face gets red/I want to cry'. Once the extremes of angry and calm are better understood, you can start addressing the emotions in between.

If the person can identify that they're getting angry, they can try to do something to calm themselves down, can remove themselves from a situation, or other people can see what is happening and take action.

For children and some adults social stories can be a useful way of explaining how to manage a certain emotion. Adults can also use the brian in hand appto manage anxiety .

Praise and reward

Many autistic people don't understand the connection between their behaviour and a punishment. Punishment won't help the person to understand what you do want, or help to teach any new skills.

Using rewards and motivators can help to encourage a particular behaviour or a new coping strategy. Even if the behaviour or task is very short, if it is followed by lots of praise and a reward, the person can feel positive about their behaviour, coping strategy or skill.

Try to give praise and rewards immediately and in a way that is meaningful to the particular person. Some people like verbal praise, others might prefer to get another kind of reward, like a sticker or a star chart, or five minutes with their favourite activity or DVD.

Consider the impact of social situations

Understanding and relating to other people, and taking part in everyday family and social life can be harder if you're autistic. Other people appear to know, intuitively, how to interact with each other, yet can also struggle to build rapport with autistic people. Unfamiliar social situations, with their unwritten rules, can be daunting and unpredictable. Some people may engage in behaviour to try to avoid social contact.

Manage change and transition times

Autistic people can find it difficult to cope with change, whether a temporary change such as needing to drive a different way to school due to roadworks, a more permanent change such as moving house , or the change from one activity to another.

Sequencing can be difficult - that is, putting what is going to happen in a day in a logical order in their mind. Abstract concepts such as time aren't easy to understand, and autistic people may find it hard to wait. You may find that behavioural difficulties occur more in transition times between activities. Using a visual timetable can often help the person to see what will be happening throughout the day. Unstructured time, such as break times at school, which can be noisy and chaotic, may be difficult to deal with.

It’s important to prepare the person in advance for what the change is likely to involve. Read about how you can help with change, sequencing, transition and breaktimes.

Find out if the person is being bullied

Autistic people are at more risk of being bullied than their peers. Some will have difficulty recognising what bullying is, and may not be able to describe what has happened. The feelings created by being bullied may lead to difficult behaviour.

Read more about bullying and what you can do.

Offer a safe space or 'time out'

A safe space, or time out can be a way to calm down, especially if environmental factors, such as flickering lights, are causing distress. This could be in a familiar place, like their bedroom, or doing a calming activity.

Build in relaxation

The person might find engaging in their special interest or favourite activity relaxing, but not being able to do their favourite activity when they want to can be the cause of behavioural difficulties. Build opportunities for relaxation, and engaging in favourite activities, into the daily routine. Relaxing activities could include looking at bubble lamps, smelling essential oils, listening to music, massages, or swinging on a swing.

Difficult behaviour can often be diffused by an activity that releases energy or pent-up anger or anxiety. This might be punching a punch bag, bouncing on a trampoline or running around the garden.

Generalise and maintain skills

Autistic people can find it difficult to transfer (or 'generalise') new skills they've learned from one situation to another. Find opportunities to use new skills or coping strategies in different situations.

Check that skills haven't been forgotten. If you have used strategies successfully in the past, it might help to revisit them from time to time. You may also need to use them during periods of stress, illness or change when old behaviours can return.